Climate anxiety is no joke. It’s as serious as, well, the challenges our climate faces thanks in large part to the profound damage human activity has inflicted upon our Earth. There’s a reason why Daily Kos has a support group devoted to it.

There is a difference, however, between expressing strong concerns about our environment and the suffering unleashed by climate change—justifiable concerns only a fool would dismiss—and the kind of debilitating feelings that accompany climate anxiety, also known as eco-anxiety, as defined by clinicians.

This type of “paralyzing panic” can lead to “hopelessness, grief, anger, guilt, and existential dread.” Climate anxiety not only harms the people experiencing it, but actually hamstrings the effectiveness of the very environmental movement those folks suffering from it so desperately want to succeed.

RELATED STORY: Fox News' efforts to deny climate change are getting comical

So what exactly do we mean by climate anxiety? One thing that’s very important to start with is this, from Harvard Medical School’s Dr. Stephanie Collier: “climate anxiety is not a mental illness.” As in, this is a legitimate issue, based in science, that is a reasonable thing to keep folks up at night. Now that we’ve made that clear, the Handbook of Climate Psychology includes the following definition of this condition: “heightened emotional, mental or somatic distress in response to dangerous changes in the climate system.”

Sarah Lowe, clinical psychologist and associate professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Yale School of Public Health, has been studying the topic in depth, and she characterized it as: “Distress about climate change … that can manifest as intrusive thoughts or feelings of distress about future disasters or the long-term future of human existence.” She added that it can “include heart racing and shortness of breath, and a behavioral component: when climate anxiety gets in the way of one’s social relationships or functioning at work or school.”

Lowe’s research partner, Anthony Leiserowitz, is the founder and director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and a senior research scientist at Yale School of the Environment. He clarified that while almost two-thirds of Americans were worried about climate change, that’s “not the same thing as anxiety. … Where worry becomes a problem is when it becomes overwhelming and debilitating, when it keeps you from living your life.” Furthermore, it’s important to give it a name, as Dr. Paolo Cianconi, who practices in the ecology psychiatry and mental health division of the World Psychiatry Association, explained: “When people start to be worried about the planet, they don’t know that they have eco-anxiety. When they see this thing has a name, then they understand what to call it.”

According to a recent survey from Leiserowitz and his colleagues at the Yale Center, approximately one in 10 Americans say they felt anxiety and/or depression due to climate change of the kind described above on multiple days over the previous two weeks. According to an international survey (1,000 respondents each from Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, India, Nigeria, Philippines, Portugal, the U.K., and the U.S.), a full half of those 16-25 years old reported feelings consistent with climate anxiety. And 55.7% of them believe that “humanity is doomed.” This is a widespread, global phenomenon we cannot ignore.

Separate from simply waiting for good news on the green front—which does exist, as we’ll explore below—there are treatments that can help those suffering from climate anxiety. People who experience it can learn to better cope with their feelings—which often connect to their own sense of powerlessness as an individual.

You don’t have to be a therapist—any of us can help someone experiencing eco-anxiety. Here’s what you can do, again from Harvard’s Dr. Collier:

Beyond what friends and family can do, professional treatment really can help. There’s even a developing specialization within the field of psychotherapy to help people suffering from climate anxiety.

Eco-anxiety does pose a particular, perhaps unique challenge compared to other forms of anxiety, such as social anxiety. Andrew Bryant, a clinical social worker whose focus is “climate-aware therapy,” explained that one can address social anxiety, for example, in small doses by interacting with one person or small groups while also working with a therapist. When it comes to climate anxiety, on the other hand, “because of the largeness of the scope, it’s really difficult to find an action step that’s going to assure people that the fear, the existential threat, is going to dissipate.”

Bryant added that, before acting, it’s vital to thoroughly process one’s feelings, to become aware of what triggers them, and practice ways to “de-escalate” the emotions before they get out of control. That will not only reduce the anxiety one feels, but also make it easier to take productive action. Additionally, experts recommend reducing the time one spends online (which can lead to “doom scrolling”) as well as focusing on what one can do today.

Dr. Thomas J. Doherty, who practices in Portland, Oregon, is a leading practitioner in the field, and he spoke to The New York Times recently about what constitutes treatment. First of all, he has argued that eco-anxiety is fundamentally different even from other forms of anxiety caused by societal factors such as crime or terrorism. Treatment requires a combination of relatively rare approaches, including ecotherapy—which delves into one’s “relationship with the natural world”—and existential therapy—which is aimed at combating despair.

The NYT article included portraits of a number of people battling climate anxiety. Alina Black, a 37-year-old woman, described experiencing severe “guilt and shame” from everything she purchased, including diapers. She felt as if she had “developed a phobia to my way of life.” She sought out Doherty, who listened to her, and then gave her information that, because of his knowledge on the topic, provided real comfort: He said, according to his notes: “In the future, even with worst-case scenarios, there will be good days. Disasters will happen in certain places. But, around the world, there will be good days. Your children will also have good days.” Black stated: “I really trust that when I hear information from him, it’s coming from a deep well of knowledge. And that gives me a lot of peace.”

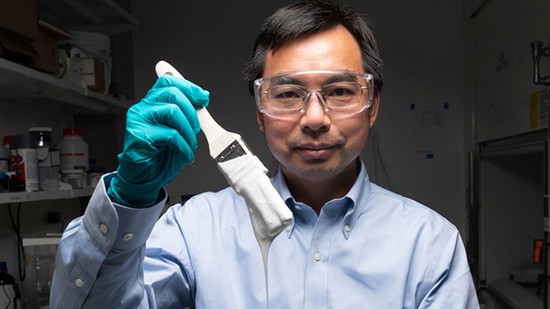

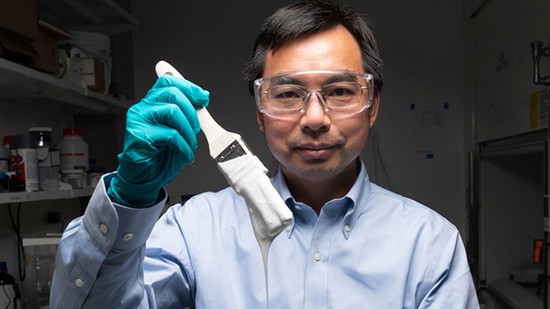

Broadening out from the sentiments Doherty expressed, there are concrete reasons for optimism. It flows from developments like this one, which is in an area I’d never even imagined could have an impact: a Purdue University mechanical engineering professor named Xiulin Ruan developed an incredible kind of white paint that can reflect a full 98% of sunlight. What does that have to do with the environment, you might ask? Well, a building covered with this paint can reduce its air conditioning usage by 40%. Not bad.

Purdue University mechanical engineering professor Xiulin Ruan

Ruan and his team have won multiple awards for their discovery. They’ve also tweaked their formula and come up with another type that can be used on vehicles, and we know how many of those there are out there. In case you’re wondering, it looks pretty much like any other white paint on the market. It should be available for purchase within a year or so. Of course, this won’t solve global warming on its own, but it can have a real impact, in particular while we make more comprehensive changes to the way we use energy by transitioning away from fossil fuels and to renewables.

Speaking of renewables, we are making real progress on this front across the board, including in new areas like geothermal energy, which Mark Sumner explored recently. Geothermal can, if it lives up to its early potential, help supplement solar and wind power by acting as an additional “base load system.”

RELATED STORY: Could kinder, gentler fracking create a breakthrough in geothermal power?

My optimism is also sparked by more well-known developments in green technology and renewable energy—fueled in part by President Joe Biden's policy achievements—passed without any Republican support, mind you. In the first 12 months after Biden signed sweeping climate legislation, the amount of money spent on “clean-energy technologies” was $213 billion—skyrocketing up from only $81 billion just two years prior. As Pulitzer Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman noted, these achievements not only invest government money directly into projects, but are also sparking “a Big Green Push, catalyzing a wave of private investment much bigger than you might have expected from the size of government outlays alone.”

RELATED STORY: Biden awards $7 billion for clean hydrogen hubs across the country to help replace fossil fuels

And it’s not just at the federal level that we’ve seen new laws passed in recent years. States where Democrats have full control, such as Colorado and Washington, among others, have taken important steps that, although they are no substitute for country-wide measures, can have an impact.

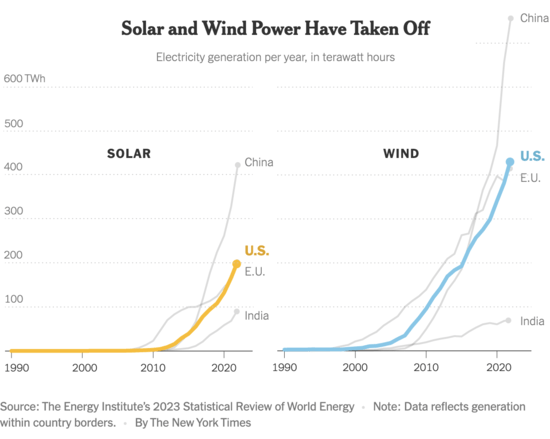

A recent New York Times feature goes into great depth on developments in renewable energy across a variety of areas. To summarize:

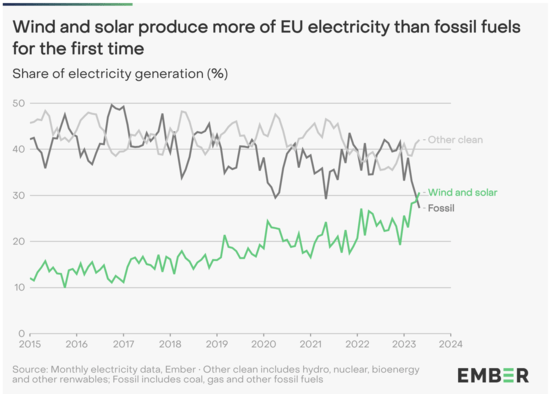

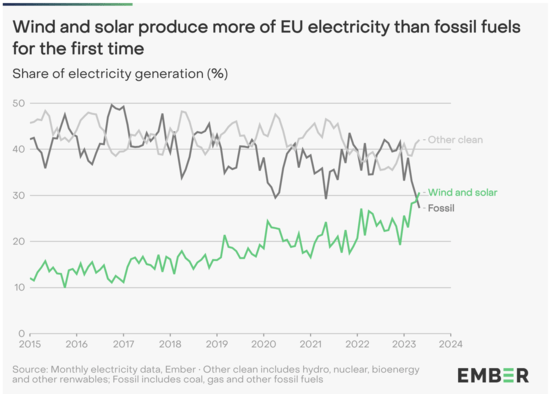

The European Union has been especially aggressive in combating climate change. For just a couple of examples, it has “strengthen[ed] its renewable energy target from a 32% share [of total energy] to 42.5% by 2030, with an additional 2.5% ‘indicative’ target,” and, in May of this year, drew more of its electricity from wind and solar than from fossil fuels over an entire month for the first time.

Is arresting climate change and preventing catastrophic damage to our environment—and to the beings who populate it—going to be easy? Of course not, and we know that one of our two major political parties stands dead-set opposed to doing so (not to mention that some in our own party—cough, Joe Manchin—aren’t all that helpful either). Feeling anxiety or depression over climate change does no good for the climate, and if anything causes harm as depression makes it harder for people to act constructively.

On the other hand, feeling like we’ve got a chance of success can help with climate anxiety and depression, thus making people feel better in their daily lives and enhancing their ability to help humanity succeed on this front. As Rebecca Solnit wrote: “Your opponents would love you to believe that it's hopeless, that you have no power, that there's no reason to act, that you can't win. Hope is a gift you don't have to surrender, a power you don't have to throw away.”

So I want to spread some good news here, and some of why I’m optimistic. And it’s not just me. As Al Gore—no Pollyanna on the environment—recently reminded us: “We know how to fix this.” Separate from oldsters like Al and me, young people—despite the grave concerns they have collectively about our environment—have hope too and are joining the fight in large numbers. They are rejecting pessimism with a cheery, “Okay, Doomer, we’ve got this.” Check out this young activist and tell me you aren’t inspired:

In short, this is an optimism that’s backed by information. The trend lines are starting to shift, and hopefully more positive developments will keep coming—as long as we don’t give up.

RELATED STORIES:

With Democratic control, Michigan's governor pushes for health care and climate change laws

Climate activists target jets, yachts and golf in global protests against the ultra rich

Ian Reifowitz is the author of The Tribalization of Politics: How Rush Limbaugh's Race-Baiting Rhetoric on the Obama Presidency Paved the Way for Trump (Foreword by Markos Moulitsas)

Campaign Action

There is a difference, however, between expressing strong concerns about our environment and the suffering unleashed by climate change—justifiable concerns only a fool would dismiss—and the kind of debilitating feelings that accompany climate anxiety, also known as eco-anxiety, as defined by clinicians.

This type of “paralyzing panic” can lead to “hopelessness, grief, anger, guilt, and existential dread.” Climate anxiety not only harms the people experiencing it, but actually hamstrings the effectiveness of the very environmental movement those folks suffering from it so desperately want to succeed.

RELATED STORY: Fox News' efforts to deny climate change are getting comical

So what exactly do we mean by climate anxiety? One thing that’s very important to start with is this, from Harvard Medical School’s Dr. Stephanie Collier: “climate anxiety is not a mental illness.” As in, this is a legitimate issue, based in science, that is a reasonable thing to keep folks up at night. Now that we’ve made that clear, the Handbook of Climate Psychology includes the following definition of this condition: “heightened emotional, mental or somatic distress in response to dangerous changes in the climate system.”

Sarah Lowe, clinical psychologist and associate professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Yale School of Public Health, has been studying the topic in depth, and she characterized it as: “Distress about climate change … that can manifest as intrusive thoughts or feelings of distress about future disasters or the long-term future of human existence.” She added that it can “include heart racing and shortness of breath, and a behavioral component: when climate anxiety gets in the way of one’s social relationships or functioning at work or school.”

Lowe’s research partner, Anthony Leiserowitz, is the founder and director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and a senior research scientist at Yale School of the Environment. He clarified that while almost two-thirds of Americans were worried about climate change, that’s “not the same thing as anxiety. … Where worry becomes a problem is when it becomes overwhelming and debilitating, when it keeps you from living your life.” Furthermore, it’s important to give it a name, as Dr. Paolo Cianconi, who practices in the ecology psychiatry and mental health division of the World Psychiatry Association, explained: “When people start to be worried about the planet, they don’t know that they have eco-anxiety. When they see this thing has a name, then they understand what to call it.”

According to a recent survey from Leiserowitz and his colleagues at the Yale Center, approximately one in 10 Americans say they felt anxiety and/or depression due to climate change of the kind described above on multiple days over the previous two weeks. According to an international survey (1,000 respondents each from Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, India, Nigeria, Philippines, Portugal, the U.K., and the U.S.), a full half of those 16-25 years old reported feelings consistent with climate anxiety. And 55.7% of them believe that “humanity is doomed.” This is a widespread, global phenomenon we cannot ignore.

Separate from simply waiting for good news on the green front—which does exist, as we’ll explore below—there are treatments that can help those suffering from climate anxiety. People who experience it can learn to better cope with their feelings—which often connect to their own sense of powerlessness as an individual.

You don’t have to be a therapist—any of us can help someone experiencing eco-anxiety. Here’s what you can do, again from Harvard’s Dr. Collier:

Validate their concerns. "I hear you, and it makes sense that you are worried (or angry) about this issue."

Help direct their efforts to advocacy groups. Spend time together researching organizations that they can get involved with.

Educate yourselves on steps you both can take to minimize your impact on the environment.

Support your loved one's decisions to make changes to their lifestyle, especially changes they can witness at home.

Spend time in nature with your family, or consider planting flowers or trees.

Beyond what friends and family can do, professional treatment really can help. There’s even a developing specialization within the field of psychotherapy to help people suffering from climate anxiety.

Eco-anxiety does pose a particular, perhaps unique challenge compared to other forms of anxiety, such as social anxiety. Andrew Bryant, a clinical social worker whose focus is “climate-aware therapy,” explained that one can address social anxiety, for example, in small doses by interacting with one person or small groups while also working with a therapist. When it comes to climate anxiety, on the other hand, “because of the largeness of the scope, it’s really difficult to find an action step that’s going to assure people that the fear, the existential threat, is going to dissipate.”

Bryant added that, before acting, it’s vital to thoroughly process one’s feelings, to become aware of what triggers them, and practice ways to “de-escalate” the emotions before they get out of control. That will not only reduce the anxiety one feels, but also make it easier to take productive action. Additionally, experts recommend reducing the time one spends online (which can lead to “doom scrolling”) as well as focusing on what one can do today.

Dr. Thomas J. Doherty, who practices in Portland, Oregon, is a leading practitioner in the field, and he spoke to The New York Times recently about what constitutes treatment. First of all, he has argued that eco-anxiety is fundamentally different even from other forms of anxiety caused by societal factors such as crime or terrorism. Treatment requires a combination of relatively rare approaches, including ecotherapy—which delves into one’s “relationship with the natural world”—and existential therapy—which is aimed at combating despair.

The NYT article included portraits of a number of people battling climate anxiety. Alina Black, a 37-year-old woman, described experiencing severe “guilt and shame” from everything she purchased, including diapers. She felt as if she had “developed a phobia to my way of life.” She sought out Doherty, who listened to her, and then gave her information that, because of his knowledge on the topic, provided real comfort: He said, according to his notes: “In the future, even with worst-case scenarios, there will be good days. Disasters will happen in certain places. But, around the world, there will be good days. Your children will also have good days.” Black stated: “I really trust that when I hear information from him, it’s coming from a deep well of knowledge. And that gives me a lot of peace.”

Broadening out from the sentiments Doherty expressed, there are concrete reasons for optimism. It flows from developments like this one, which is in an area I’d never even imagined could have an impact: a Purdue University mechanical engineering professor named Xiulin Ruan developed an incredible kind of white paint that can reflect a full 98% of sunlight. What does that have to do with the environment, you might ask? Well, a building covered with this paint can reduce its air conditioning usage by 40%. Not bad.

Purdue University mechanical engineering professor Xiulin Ruan

Ruan and his team have won multiple awards for their discovery. They’ve also tweaked their formula and come up with another type that can be used on vehicles, and we know how many of those there are out there. In case you’re wondering, it looks pretty much like any other white paint on the market. It should be available for purchase within a year or so. Of course, this won’t solve global warming on its own, but it can have a real impact, in particular while we make more comprehensive changes to the way we use energy by transitioning away from fossil fuels and to renewables.

Speaking of renewables, we are making real progress on this front across the board, including in new areas like geothermal energy, which Mark Sumner explored recently. Geothermal can, if it lives up to its early potential, help supplement solar and wind power by acting as an additional “base load system.”

RELATED STORY: Could kinder, gentler fracking create a breakthrough in geothermal power?

My optimism is also sparked by more well-known developments in green technology and renewable energy—fueled in part by President Joe Biden's policy achievements—passed without any Republican support, mind you. In the first 12 months after Biden signed sweeping climate legislation, the amount of money spent on “clean-energy technologies” was $213 billion—skyrocketing up from only $81 billion just two years prior. As Pulitzer Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman noted, these achievements not only invest government money directly into projects, but are also sparking “a Big Green Push, catalyzing a wave of private investment much bigger than you might have expected from the size of government outlays alone.”

RELATED STORY: Biden awards $7 billion for clean hydrogen hubs across the country to help replace fossil fuels

And it’s not just at the federal level that we’ve seen new laws passed in recent years. States where Democrats have full control, such as Colorado and Washington, among others, have taken important steps that, although they are no substitute for country-wide measures, can have an impact.

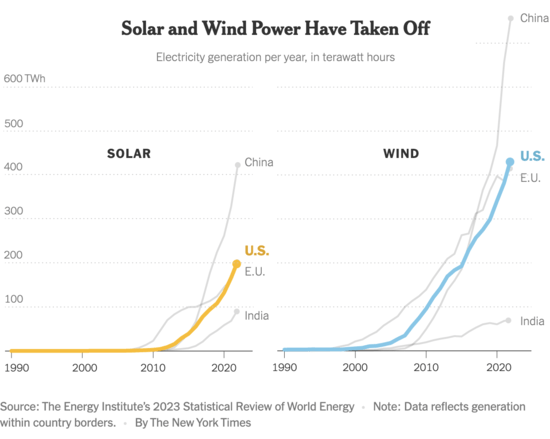

A recent New York Times feature goes into great depth on developments in renewable energy across a variety of areas. To summarize:

Across the country, a profound shift is taking place that is nearly invisible to most Americans. The nation that burned coal, oil and gas for more than a century to become the richest economy on the planet, as well as historically the most polluting, is rapidly shifting away from fossil fuels.

A similar energy transition is already well underway in Europe and elsewhere. But the United States is catching up, and globally, change is happening at a pace that is surprising even the experts who track it closely.

The European Union has been especially aggressive in combating climate change. For just a couple of examples, it has “strengthen[ed] its renewable energy target from a 32% share [of total energy] to 42.5% by 2030, with an additional 2.5% ‘indicative’ target,” and, in May of this year, drew more of its electricity from wind and solar than from fossil fuels over an entire month for the first time.

Is arresting climate change and preventing catastrophic damage to our environment—and to the beings who populate it—going to be easy? Of course not, and we know that one of our two major political parties stands dead-set opposed to doing so (not to mention that some in our own party—cough, Joe Manchin—aren’t all that helpful either). Feeling anxiety or depression over climate change does no good for the climate, and if anything causes harm as depression makes it harder for people to act constructively.

On the other hand, feeling like we’ve got a chance of success can help with climate anxiety and depression, thus making people feel better in their daily lives and enhancing their ability to help humanity succeed on this front. As Rebecca Solnit wrote: “Your opponents would love you to believe that it's hopeless, that you have no power, that there's no reason to act, that you can't win. Hope is a gift you don't have to surrender, a power you don't have to throw away.”

So I want to spread some good news here, and some of why I’m optimistic. And it’s not just me. As Al Gore—no Pollyanna on the environment—recently reminded us: “We know how to fix this.” Separate from oldsters like Al and me, young people—despite the grave concerns they have collectively about our environment—have hope too and are joining the fight in large numbers. They are rejecting pessimism with a cheery, “Okay, Doomer, we’ve got this.” Check out this young activist and tell me you aren’t inspired:

Spinning the fear and frustration that many young people experience into positive action is a chief aim of Wanjiku Gatheru, 24, who founded an organization called Black Girl Environmentalist that is working to get more young people of color involved in the movement.

“Fear doesn’t motivate people toward sustainable action,” Ms. Gatheru said. “Providing solutions in the midst of discussion of a problem helps get people engaged.”

In short, this is an optimism that’s backed by information. The trend lines are starting to shift, and hopefully more positive developments will keep coming—as long as we don’t give up.

RELATED STORIES:

With Democratic control, Michigan's governor pushes for health care and climate change laws

Climate activists target jets, yachts and golf in global protests against the ultra rich

Ian Reifowitz is the author of The Tribalization of Politics: How Rush Limbaugh's Race-Baiting Rhetoric on the Obama Presidency Paved the Way for Trump (Foreword by Markos Moulitsas)

Campaign Action