I finally finished the “Barbenheimer” trend that everyone else did this past summer. Although I wanted to take my wife to see the “Barbie” movie, I really didn’t have any interest in "Oppenheimer." I feared the movie would make him into some sort of hero. Yet to director Christopher Nolan’s credit, the film showcased how flawed a person Oppenheimer was: his arrogance, his adultery, his penchant for indifference, and his righteous moralization against nuclear proliferation—but only after his team had built the weapon. The film also didn’t hide Oppenheimer’s empathy toward communism.

The movie had powerful moments. One of the hardest to watch was the discussion that was had on where to drop the bombs. We learned why Japanese military targets were ignored and the reason Kyoto was taken off the list. Yet as powerful as the motion picture was, and despite being over three hours long, the film left a lot out. For example, it failed to include the voices of Japanese victims, but at least they were acknowledged in a haunting scene when Oppenheimer was trying to enjoy his success. (The film never actually shows the devastation of Hiroshima or Nagasaki.) Unfortunately, there was an equally compelling narrative closer to home that was all but ignored: that of New Mexico’s own residents.

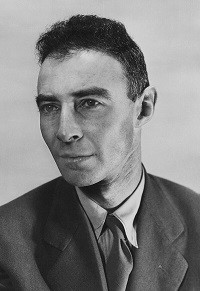

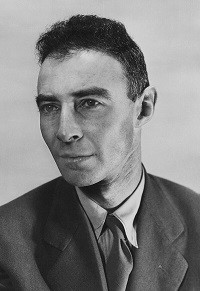

Robert J. Oppenheimer

The film portrays the Trinity Test, the world’s first nuclear test, as occurring in a remote and uninhabited landscape, which echoed what the government claimed at the time. In fact, there is a line in the film where Oppenheimer says the only thing near the site was a boy’s school and a burial site. This couldn't be further from the truth. Many people called that area their home, including many Hispano and Indigenous communities with deep historical roots in the region. The U.S. military, along with Oppenheimer himself, knew that Nuevo Mexicano and Mescalero Apache families had farms near that area.

Eminent domain was used to seize their land for the nuclear test, sometimes at gunpoint, with promises of fair compensation that often went unfulfilled. Those few who did receive money for their property received substantially less than nearby white landowners. The land owned by an Anglo entrepreneur was acquired at a rate of $43 per acre, whereas Hispanic homesteaders received as little as $7 per acre

Farms were bulldozed, livestock was shot, and there were even violent confrontations with military police. After forcibly being uprooted from their homes, being given less than 24 hours to leave with what they could carry, and having nowhere to turn, the men displaced by the nuclear test were compelled to work at the very laboratory responsible for their displacement. In this workplace, they were tasked by Oppenheimer to handle beryllium, a critical metal in the development of nuclear reactors and the production of plutonium used in the Trinity Test. Sadly, beryllium is a toxic substance that can lead to debilitating conditions. What makes this even more distressing is the fact that the Hispano men, unlike their white counterparts, were given no protective gear to wear. All of them tragically succumbed to berylliosis.

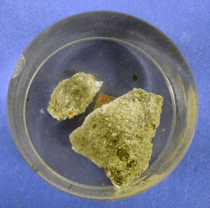

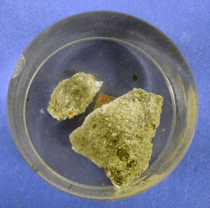

Trinitite sample, fused sand, from the first nuclear test on July 16, 1945

Seventy-five years later, the descendants of those families are still grappling with the devastating consequences of exposure to radioactive fallout. Their stories, long ignored by our government, demand acknowledgment and compensation. Although the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) established an administrative program for claims relating to atmospheric nuclear testing, incredibly, these people were specifically exempted from receiving compensation. There is currently a bill in Congress that would expand to help them, but RECA is due to expire by 2024 (it was extended for a year), and time is running out for the help they deserved decades ago.

This would have made a great scene in the film. In the cool dawn of a July morning in 1945, 11-year-old Henry Herrera was helping his father out in the field. He and his father watched in awe as a blinding light illuminated the sky, followed by a deafening boom. They had no idea what it was. Just a few hours later, their home and field were completely covered in ash. "My mother had just hung her white clothes on the clothesline, and god dang! You should have seen the god dang dust that rolled all over town. She was so mad that she had to wash them all over again," recalls Herrera to Axios. What Henry’s mother didn’t know was that those clothes were now radioactive, and yet they continued using them for years.

Curious locals, wondering what happened, eventually ventured to ground zero. There was no effort from the U.S. government to block access or to warn anyone of the dangers of doing so. Residents found bright green pieces of glass that sparkled, and collected them. They even used the material to weave into jewelry and onto christening dresses. The glass was actually trinitite, a residue left from the plutonium-based nuclear blast that melted and fused into the sand. They had no idea it was radioactive.

Tragically, the residents remained unaware of the true nature of the Trinity Test until the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki a month later. It was only then that they began connecting the dots, realizing the grave consequences of their proximity to the nuclear test that unleashed a cascade of suffering upon their community for generations to come.

The U.S. Army had completely underestimated the effects of the atomic bomb they detonated at Jornada del Muerto, a desert valley known as the Route of the Dead. The shockwaves reached as far as Tularosa and sent residents on the Mescalero Apache Reservation into hiding.

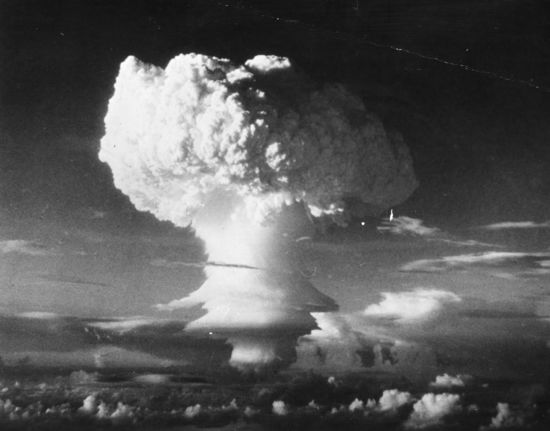

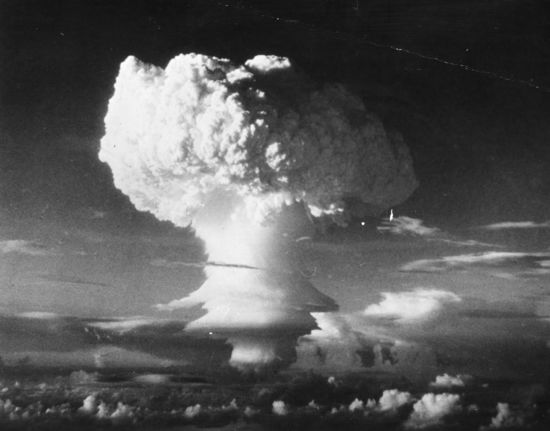

Mushroom cloud from a government nuclear test in 1952

Initially, the radioactive cloud drifted away from the Hispanic villages and Indigenous communities. However, the unpredictable winds of New Mexico brought it back, blanketing these communities with radioactive debris.

The aftermath of the Trinity Test had devastating health repercussions, with families in New Mexico enduring the legacy of cancer spanning multiple generations since 1945. Henry Herrera had to undergo jaw reconstruction as a result of mouth cancer. All of the families suddenly had to grapple with a massive financial burden of medical treatment, completely unaware of the root cause of their affliction.

Even more tragically, New Mexicans exposed to Trinity's radioactive fallout weren’t eligible for compensation under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), the federal law that provided billions of dollars to individuals exposed during subsequent tests or those exposed during uranium mining. After the atomic bomb went off, children unknowingly played in contaminated water, and livestock drank from radioactive aquifers. Residents suffered from cancer, miscarriages, and many unexplained illnesses. Yet those impacted by the initial test were exempted from compensation. Tina Cordova, a cancer survivor and co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders, said the exclusion was based on racism: “This is a social justice issue. We want acknowledgment that the federal government did this without our consent then forgot about us and left us to fend for ourselves.”

Beyond the Trinity Test, the Manhattan Project's dark legacy extends to the Navajo Nation, where uranium mining became a huge industry for nuclear weapons and energy. Navajo workers were kept in the dark about the dangers, and suddenly suffered high rates of health issues like various cancers and kidney failure. To this day, abandoned uranium mines still contaminate Navajo waterways with toxic metals.

For those lucky enough to get RECA compensation, there is a wide range of conditions that weren’t covered, such as kidney tissue injury and nephritis, because of the lack of data connecting those diseases to radiation. RECA also refused to cover Navajo miners after December 1971, when the United States government was no longer the sole purchaser of uranium ore and the mines were opened to commercial interests. Today, the RECA program is as relevant and utilized as it ever was, with over 53,000 claims being filed as of August of last year. A good portion of those claims are Indigenous people like the Navajo.

Hollywood had no trouble celebrating the Navajo code talkers during World War II, but although the Oppenheimer movie provided a chance to showcase another part of their history that was just as patriotic and dangerous, it was passed over. I can’t help but wonder if one of the reasons was that it really didn’t paint our government in the best light.

RECA was set to expire July 10, 2022, but Democratic Sen. Ben Ray Luján of New Mexico was able to secure a two-year extension, which President Joe Biden signed into law. Luján has been pushing RECA legislation and amendments every term he’s served in office. His new amendment would update the RECA program to cover more people, to include those impacted by the Trinity Test 78 years ago. It would expand eligibility to people beyond Arizona, Nevada, and Utah, and would finally compensate former industry workers, most of whom are members of the Navajo Nation.

Thankfully, his amendment passed the Senate in a bipartisan fashion this past August. Unfortunately, it is not a part of any House bill, as the current House majority doesn’t seem at all interested in actually legislating. Hopefully, the House and Senate Armed Services Committees will work out the RECA language in their reconciliation for the upcoming budget fight. My fear is that this will become a casualty of the Freedom Caucus’ budget war—especially since it’s about spending money to help minority victims.

Let your elected officials know that you are watching. You can do your part in encouraging your representative to sign on to expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act.

Protest at White Mesa Uranium Mill

The Navajo Nation, Hispanos, and other Indigenous communities have suffered long enough. Native American communities have routinely suffered the brunt of environmental pollution, from the dumping of toxic waste on their land to being forced to fight multiple tar sand pipelines through sensitive areas regardless of treaties promising their sovereignty.

Just last year, citizens of multiple tribal nations traveled to White Mesa, Utah, to protest a corporate uranium mill's sprawling waste pits that have polluted the local tribe's water supply. The mill has had a long history of discarding waste that has contaminated the local Indigenous lands.

The least our leaders can do is acknowledge the severe health conditions and the suffering that is still happening as the result of purposely exposing people to dangerous levels of radiation. Being left out of the latest Hollywood summer blockbuster is one thing, but I can’t excuse them being ignored any longer by our government.

RELATED STORY: A prominent museum obtained items from a massacre of Native Americans. Descendants want them back

Campaign Action

The movie had powerful moments. One of the hardest to watch was the discussion that was had on where to drop the bombs. We learned why Japanese military targets were ignored and the reason Kyoto was taken off the list. Yet as powerful as the motion picture was, and despite being over three hours long, the film left a lot out. For example, it failed to include the voices of Japanese victims, but at least they were acknowledged in a haunting scene when Oppenheimer was trying to enjoy his success. (The film never actually shows the devastation of Hiroshima or Nagasaki.) Unfortunately, there was an equally compelling narrative closer to home that was all but ignored: that of New Mexico’s own residents.

Robert J. Oppenheimer

The film portrays the Trinity Test, the world’s first nuclear test, as occurring in a remote and uninhabited landscape, which echoed what the government claimed at the time. In fact, there is a line in the film where Oppenheimer says the only thing near the site was a boy’s school and a burial site. This couldn't be further from the truth. Many people called that area their home, including many Hispano and Indigenous communities with deep historical roots in the region. The U.S. military, along with Oppenheimer himself, knew that Nuevo Mexicano and Mescalero Apache families had farms near that area.

Eminent domain was used to seize their land for the nuclear test, sometimes at gunpoint, with promises of fair compensation that often went unfulfilled. Those few who did receive money for their property received substantially less than nearby white landowners. The land owned by an Anglo entrepreneur was acquired at a rate of $43 per acre, whereas Hispanic homesteaders received as little as $7 per acre

Farms were bulldozed, livestock was shot, and there were even violent confrontations with military police. After forcibly being uprooted from their homes, being given less than 24 hours to leave with what they could carry, and having nowhere to turn, the men displaced by the nuclear test were compelled to work at the very laboratory responsible for their displacement. In this workplace, they were tasked by Oppenheimer to handle beryllium, a critical metal in the development of nuclear reactors and the production of plutonium used in the Trinity Test. Sadly, beryllium is a toxic substance that can lead to debilitating conditions. What makes this even more distressing is the fact that the Hispano men, unlike their white counterparts, were given no protective gear to wear. All of them tragically succumbed to berylliosis.

Trinitite sample, fused sand, from the first nuclear test on July 16, 1945

Seventy-five years later, the descendants of those families are still grappling with the devastating consequences of exposure to radioactive fallout. Their stories, long ignored by our government, demand acknowledgment and compensation. Although the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) established an administrative program for claims relating to atmospheric nuclear testing, incredibly, these people were specifically exempted from receiving compensation. There is currently a bill in Congress that would expand to help them, but RECA is due to expire by 2024 (it was extended for a year), and time is running out for the help they deserved decades ago.

This would have made a great scene in the film. In the cool dawn of a July morning in 1945, 11-year-old Henry Herrera was helping his father out in the field. He and his father watched in awe as a blinding light illuminated the sky, followed by a deafening boom. They had no idea what it was. Just a few hours later, their home and field were completely covered in ash. "My mother had just hung her white clothes on the clothesline, and god dang! You should have seen the god dang dust that rolled all over town. She was so mad that she had to wash them all over again," recalls Herrera to Axios. What Henry’s mother didn’t know was that those clothes were now radioactive, and yet they continued using them for years.

Curious locals, wondering what happened, eventually ventured to ground zero. There was no effort from the U.S. government to block access or to warn anyone of the dangers of doing so. Residents found bright green pieces of glass that sparkled, and collected them. They even used the material to weave into jewelry and onto christening dresses. The glass was actually trinitite, a residue left from the plutonium-based nuclear blast that melted and fused into the sand. They had no idea it was radioactive.

Tragically, the residents remained unaware of the true nature of the Trinity Test until the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki a month later. It was only then that they began connecting the dots, realizing the grave consequences of their proximity to the nuclear test that unleashed a cascade of suffering upon their community for generations to come.

The U.S. Army had completely underestimated the effects of the atomic bomb they detonated at Jornada del Muerto, a desert valley known as the Route of the Dead. The shockwaves reached as far as Tularosa and sent residents on the Mescalero Apache Reservation into hiding.

Mushroom cloud from a government nuclear test in 1952

Initially, the radioactive cloud drifted away from the Hispanic villages and Indigenous communities. However, the unpredictable winds of New Mexico brought it back, blanketing these communities with radioactive debris.

The aftermath of the Trinity Test had devastating health repercussions, with families in New Mexico enduring the legacy of cancer spanning multiple generations since 1945. Henry Herrera had to undergo jaw reconstruction as a result of mouth cancer. All of the families suddenly had to grapple with a massive financial burden of medical treatment, completely unaware of the root cause of their affliction.

Even more tragically, New Mexicans exposed to Trinity's radioactive fallout weren’t eligible for compensation under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), the federal law that provided billions of dollars to individuals exposed during subsequent tests or those exposed during uranium mining. After the atomic bomb went off, children unknowingly played in contaminated water, and livestock drank from radioactive aquifers. Residents suffered from cancer, miscarriages, and many unexplained illnesses. Yet those impacted by the initial test were exempted from compensation. Tina Cordova, a cancer survivor and co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders, said the exclusion was based on racism: “This is a social justice issue. We want acknowledgment that the federal government did this without our consent then forgot about us and left us to fend for ourselves.”

Beyond the Trinity Test, the Manhattan Project's dark legacy extends to the Navajo Nation, where uranium mining became a huge industry for nuclear weapons and energy. Navajo workers were kept in the dark about the dangers, and suddenly suffered high rates of health issues like various cancers and kidney failure. To this day, abandoned uranium mines still contaminate Navajo waterways with toxic metals.

For those lucky enough to get RECA compensation, there is a wide range of conditions that weren’t covered, such as kidney tissue injury and nephritis, because of the lack of data connecting those diseases to radiation. RECA also refused to cover Navajo miners after December 1971, when the United States government was no longer the sole purchaser of uranium ore and the mines were opened to commercial interests. Today, the RECA program is as relevant and utilized as it ever was, with over 53,000 claims being filed as of August of last year. A good portion of those claims are Indigenous people like the Navajo.

Hollywood had no trouble celebrating the Navajo code talkers during World War II, but although the Oppenheimer movie provided a chance to showcase another part of their history that was just as patriotic and dangerous, it was passed over. I can’t help but wonder if one of the reasons was that it really didn’t paint our government in the best light.

RECA was set to expire July 10, 2022, but Democratic Sen. Ben Ray Luján of New Mexico was able to secure a two-year extension, which President Joe Biden signed into law. Luján has been pushing RECA legislation and amendments every term he’s served in office. His new amendment would update the RECA program to cover more people, to include those impacted by the Trinity Test 78 years ago. It would expand eligibility to people beyond Arizona, Nevada, and Utah, and would finally compensate former industry workers, most of whom are members of the Navajo Nation.

Thankfully, his amendment passed the Senate in a bipartisan fashion this past August. Unfortunately, it is not a part of any House bill, as the current House majority doesn’t seem at all interested in actually legislating. Hopefully, the House and Senate Armed Services Committees will work out the RECA language in their reconciliation for the upcoming budget fight. My fear is that this will become a casualty of the Freedom Caucus’ budget war—especially since it’s about spending money to help minority victims.

Let your elected officials know that you are watching. You can do your part in encouraging your representative to sign on to expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act.

Protest at White Mesa Uranium Mill

The Navajo Nation, Hispanos, and other Indigenous communities have suffered long enough. Native American communities have routinely suffered the brunt of environmental pollution, from the dumping of toxic waste on their land to being forced to fight multiple tar sand pipelines through sensitive areas regardless of treaties promising their sovereignty.

Just last year, citizens of multiple tribal nations traveled to White Mesa, Utah, to protest a corporate uranium mill's sprawling waste pits that have polluted the local tribe's water supply. The mill has had a long history of discarding waste that has contaminated the local Indigenous lands.

The least our leaders can do is acknowledge the severe health conditions and the suffering that is still happening as the result of purposely exposing people to dangerous levels of radiation. Being left out of the latest Hollywood summer blockbuster is one thing, but I can’t excuse them being ignored any longer by our government.

RELATED STORY: A prominent museum obtained items from a massacre of Native Americans. Descendants want them back

Campaign Action