If you have only read the headlines of the Justice Department’s scathing 89-page report of the Minneapolis Police Department released Friday, you should dig deeper.

It’s not that what’s revealed is surprising given all we’ve read about, heard about, or lived firsthand over the years. After all, unjustified police use of excessive force, including deadly force, against Black Americans and American Indians and other people of color is a national pastime with a long and ugly history. The MPD is just one actor in a cast of thousands in police departments from coast to coast. But not surprising doesn’t mean not shocking, not sickening, not infuriating. Deep into the 21st century, the fact we still haven’t curtailed the racist behavior and rotten leadership detailed in the report is shocking and dispiriting.

Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke, who led the U.S. Justice Department’s team that investigated the Minneapolis Police Department after the police murder of George Floyd in 2020.

The federal findings reinforce the findings of a state investigation into MPD practices after veteran officer Derek Chauvin three years ago murdered George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, touching off a massive, nationwide outpouring of protests by hundreds of thousands of people of all races.

The DOJ report found that the department engages in a “pattern or practice of conduct that deprives people of their rights under the Constitution and federal law.” Among other things, the MPD “unlawfully discriminates against Black and Native American people … violates the rights of people engaged in protected speech … [and] discriminate against people with behavioral health disabilities when responding to calls for assistance.” The review also found that “roughly three quarters of MPD’s reported uses of force did not involve an associated violent offense or a weapons offense.”

And, the authors lament, “this report is not the first to identify racial disparities in MPD’s law enforcement activities. Over the last decade, multiple reports have identified racial disparities in MPD’s data on stops, searches, and uses of force similar to those we identify in this report.” They also point out that while some reforms have been undertaken by the MPD, they are “insufficient” for achieving the comprehensive changes that are needed.

The report is filled with specific instances of racist attitudes, including the one that Attorney General Merrick Garland highlighted in his Friday morning announcement of the findings. He said that Minneapolis police stopped a car carrying four Somali American teens. Garland said that “one officer told them, ‘Do you remember what happened in “Blackhawk Down” when we killed a bunch of your folk? I’m proud of that. We didn’t finish the job over there. If we had, you guys wouldn’t be over here right now’.” The “Blackhawk Down” incident occurred in Mogadishu during the U.S. intervention in the Somali Civil War in 1993.

A small group of protesters marches after former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was sentenced to 22.5 years in prison for the murder of George Floyd.

And there’s this: “We found numerous incidents in which officers responded to a person’s statement that they could not breathe with a version of, ‘You can breathe; you’re talking right now.’” That was what George Floyd told officers as Chauvin pressed a knee into his neck for nine minutes until he died as bystanders looked on in horror.

Here’s more:

Page after page provide the details.

On MSNBC Friday night, Alex Wagner focused on the report in an interview with psychology professor Phillip Atiba Goff, chair of African American studies at Yale University, and co-founder of the Center for Policing Equity. (Wagner’s questions have been lightly edited for succinctness and clarity. Any transcription typos or other errors are mine alone—MB.)

In the wake of Floyd’s murder, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered removal from state police training materials instructions on use of a hold that stops blood flow to the brain. While that wasn’t what killed Floyd, the knee on the neck that took his life brought to mind for Newsom and many anti-police violence advocates the sanctioned chokehold that has killed uncounted numbers of people detained by police. Before Newsom’s action, several San Diego County agencies and the city of Minneapolis had also banned its use.

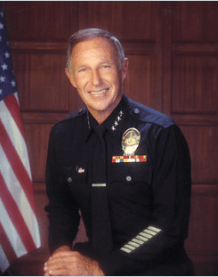

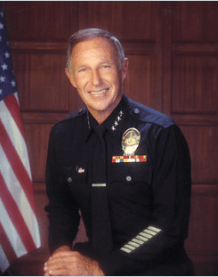

The late Daryl Gates, LAPD chief from 1978 to 1992.

Complaints about the chokehold aren’t new to California or elsewhere. Between 1975 and 1982, 16 people died from chokeholds delivered by officers of the Los Angeles Police Department, 12 of them Black men. “There was a pattern to it,” said Earl Ofari Hutchinson, director of the Los Angeles Urban Policy Roundtable. “You had the police continuing to use this chokehold and the victims were young African-American males. People were saying, ‘You are targeting us with a hold that has deadly consequence.’ ” The police chief at the time, Daryl Gates, made matters worse in 1982 when he said, ''It seems to me that we may be finding that in some Blacks when [the chokehold] is applied, the veins or the arteries do not open as fast as they do on normal people.'' The NAACP sought his suspension for that and other behavior, but Gates continued with the department for another decade.

Though they obviously can be lethal, the chokehold and knees on necks are just symptoms of the problems with modern policing nationwide. A far stickier problem is how to root out racists and keep chiefs like Gates and rank-and-filers like Chauvin from remaining on duty for decades in police departments throughout the nation. And also how to keep them from getting jobs with new departments after being fired despite their records of abuse of power, excessive force, or other wrongdoing in their interactions with the people they are supposed to protect.

As Goff points out, we’re not going to fix the situation with just three DOJ investigations each year of the thousands of U.S. police departments. We desperately need that realignment toward more nurturing investments that he lays out as substitutes for yet more investment in punishment. Every political candidate—whether running for city council or the presidency—should not be allowed to evade answering the question that Wagner asked: Will policing in the 21st century look different than it did in the 20th and 19th centuries? There’s no excuse for continuing down the same path we’ve traveled for hundreds of years.

Whether it’s Minneapolis or Albuquerque or Pittsburgh or East Haven or Seattle or New Orleans or Meridian or Los Angeles County or Maricopa County, consent decrees may well be “better than nothing.” But another dash of weak sauce just isn’t enough.

•••••••••••

Related:

It’s not that what’s revealed is surprising given all we’ve read about, heard about, or lived firsthand over the years. After all, unjustified police use of excessive force, including deadly force, against Black Americans and American Indians and other people of color is a national pastime with a long and ugly history. The MPD is just one actor in a cast of thousands in police departments from coast to coast. But not surprising doesn’t mean not shocking, not sickening, not infuriating. Deep into the 21st century, the fact we still haven’t curtailed the racist behavior and rotten leadership detailed in the report is shocking and dispiriting.

Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke, who led the U.S. Justice Department’s team that investigated the Minneapolis Police Department after the police murder of George Floyd in 2020.

The federal findings reinforce the findings of a state investigation into MPD practices after veteran officer Derek Chauvin three years ago murdered George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, touching off a massive, nationwide outpouring of protests by hundreds of thousands of people of all races.

The DOJ report found that the department engages in a “pattern or practice of conduct that deprives people of their rights under the Constitution and federal law.” Among other things, the MPD “unlawfully discriminates against Black and Native American people … violates the rights of people engaged in protected speech … [and] discriminate

And, the authors lament, “this report is not the first to identify racial disparities in MPD’s law enforcement activities. Over the last decade, multiple reports have identified racial disparities in MPD’s data on stops, searches, and uses of force similar to those we identify in this report.” They also point out that while some reforms have been undertaken by the MPD, they are “insufficient” for achieving the comprehensive changes that are needed.

The report is filled with specific instances of racist attitudes, including the one that Attorney General Merrick Garland highlighted in his Friday morning announcement of the findings. He said that Minneapolis police stopped a car carrying four Somali American teens. Garland said that “one officer told them, ‘Do you remember what happened in “Blackhawk Down” when we killed a bunch of your folk? I’m proud of that. We didn’t finish the job over there. If we had, you guys wouldn’t be over here right now’.” The “Blackhawk Down” incident occurred in Mogadishu during the U.S. intervention in the Somali Civil War in 1993.

A small group of protesters marches after former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was sentenced to 22.5 years in prison for the murder of George Floyd.

And there’s this: “We found numerous incidents in which officers responded to a person’s statement that they could not breathe with a version of, ‘You can breathe; you’re talking right now.’” That was what George Floyd told officers as Chauvin pressed a knee into his neck for nine minutes until he died as bystanders looked on in horror.

Here’s more:

- MPD disproportionately stops Black and Native American people and patrols differently based on the racial composition of the neighborhood, without a legitimate, related safety rationale.

- MPD discriminates during stops when deciding who to search, conducting more searches during stops involving Black and Native American people than during stops involving white people who are engaged in similar behavior.

- MPD disproportionately uses force against Black and Native American people. MPD discriminates during stops by using force more frequently during stops involving Black and Native American people than stops involving white people engaged in similar behavior.

- The percentage of stops for which MPD officers documented race sharply declined following George Floyd’s death, and MPD failed to take appropriate action to address these policy violations.

- Though MPD has long been on notice about racial disparities and officers’ failure to document data on race during stops, and was made aware of expressions of racial bias by some MPD officers and supervisors, MPD has insufficiently addressed these issues.

Page after page provide the details.

On MSNBC Friday night, Alex Wagner focused on the report in an interview with psychology professor Phillip Atiba Goff, chair of African American studies at Yale University, and co-founder of the Center for Policing Equity. (Wagner’s questions have been lightly edited for succinctness and clarity. Any transcription typos or other errors are mine alone—MB.)

Wagner: At this point, maybe it shouldn’t be striking, the animus, the deep-seated hatred some of these officers have for the community that they’re supposed to protect. What did you make of this report?

Goff: Yeah, it’s ugly. If it doesn’t shock your conscience, then you’ve been looking at too much that’s dirty for the soul. It should feel shocking and disgusting and ugly. What I made of the report is that it looks—first of all, thank goodness for Kristen Clarke and for the good women, men, and non-binary folks in the special litigation unit that do incredibly thankless work that makes this possible, that allows us to read this kind of stuff. But also thank goodness for the men, women, and non-binary folks in the Minnesota Human Rights Department that did a very similar report that also led to a negotiated consent degree in the state back in March. I’m very glad that these kinds of things are available to communities that need something like remedy after all of this ugliness.

But the thing that strikes me the most is that I’m hearing people talk about, well, that this is some measure of justice, this is some measure forward, without considering the scale of the problem. It’s not just the ugliness of these incidents, but we have about 18,000 law enforcement agencies across across the United States. And the U.S. government at best, when it was doing the most of these, under Obama did about three investigations a year. We’ve got eight open right now. You’re not going get to 18,000 three a year. And I’ve gotta say, Minneapolis, as ugly and disgusting—we worked there, I know that department very well—as ugly and disgusting as parts of it are, it’s not in top 50 worst police departments in the country. So if we’re gonna really solve what is a national problem, we’ve got to have more than just this one federal remedy for it.

Wagner: There are more than a dozen police departments under consent degrees that go back decades. First of all, just tell me about what your general opinion is of consent decrees. I think today that they plan to place the Minneapolis Police Department under a consent decree. To your mind, how effective are they? And for people who don’t really understand what they are, let’s start with what they are and how effective they are.

Goff: Sure. So, in 1994, the much-maligned crime bill—the ‘94 crime bill that Biden, for better or for worse, gets tons of credit for—gives the provisions [so the] federal government can go in and investigate and then use its power to essentially regulate out-of-control law enforcement with an investigation and then a consent decree. The consent decree is the parties get together, they say this is what we’re going to do to solve all these hideous problems that just came to light from the investigation. And usually there is a monitor that’s put into place to regulate, yes, the department is in compliance with that. So the idea is that there is a plan that’s negotiated that gets the department from the terrible place that they’re to a better place.

It clearly has not fixed the departments that have been under a consent decree. Also it is clearly better than nothing. There are things that happen under a consent decree, and both the folks in these communities and the law enforcement leaders that are there will tell you they couldn’t have gotten done if the federal government didn’t get involved. But it is weak sauce compared to the size and the scope of the problem in an individual department, much less than the problem that we’ve got nationally.

So while I’m glad that it happens—and, again, hats off to DOJ, Civil Rights [Commissioner] Kristen Clarke and her team—it is so small compared to what we see and what we’re literally reading about as to be another indictment on our capacity to hold departments and institutions accountable when they engage in such explicitly white supremacist violence.

Wagner: You can’t ignore the origins of policing in this country, the slave patrol origins, right? The question is, and I know this is asking sort of the impossible of you, but whether you think we’re at the point in the conversation around criminal justice and policing and what it means to have a safe community, where policing in the 21st century will look different than it did in the 20th and 19th centuries?

Goff: So that is a moral question of the country you’re asking there, Alex. Cause if we want things to actually change, it has to. But do I think there is enough momentum amongst our electeds? I gotta say, I wish I felt more optimistic than I [do].

We see experiment after experiment, initiative after initiative across the country, where instead of investing in more punishment, we’re investing upstream, investing in mental health resources, investing in homelessness resources—which is to say, housing—investing in after-school programs. And, lo and behold, we get less crime on the other end of that.

So what would it look like if we invested in care instead of punishment for our most vulnerable communities? We have no idea, for as a nation we have failed to do that. And if we don’t, what I really worry about for this next electoral cycle, in fact, in 2024 is that just like we almost saw in 2022, there’ll be the same playbook where folks weaponize the fear of brown people coming to your neighborhood and committing crimes. And the result of that will be a further investment across the board, left and right, in this country in more punishment. We’re going to see more of the same that, until there’s more investigations like this and more terrible readings like this that the attorney general reads out, we’re going to pretend that we couldn’t see coming when we’ve done this for literally hundreds of years in this country.

In the wake of Floyd’s murder, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered removal from state police training materials instructions on use of a hold that stops blood flow to the brain. While that wasn’t what killed Floyd, the knee on the neck that took his life brought to mind for Newsom and many anti-police violence advocates the sanctioned chokehold that has killed uncounted numbers of people detained by police. Before Newsom’s action, several San Diego County agencies and the city of Minneapolis had also banned its use.

The late Daryl Gates, LAPD chief from 1978 to 1992.

Complaints about the chokehold aren’t new to California or elsewhere. Between 1975 and 1982, 16 people died from chokeholds delivered by officers of the Los Angeles Police Department, 12 of them Black men. “There was a pattern to it,” said Earl Ofari Hutchinson, director of the Los Angeles Urban Policy Roundtable. “You had the police continuing to use this chokehold and the victims were young African-American males. People were saying, ‘You are targeting us with a hold that has deadly consequence.’ ” The police chief at the time, Daryl Gates, made matters worse in 1982 when he said, ''It seems to me that we may be finding that in some Blacks when [the chokehold] is applied, the veins or the arteries do not open as fast as they do on normal people.'' The NAACP sought his suspension for that and other behavior, but Gates continued with the department for another decade.

Though they obviously can be lethal, the chokehold and knees on necks are just symptoms of the problems with modern policing nationwide. A far stickier problem is how to root out racists and keep chiefs like Gates and rank-and-filers like Chauvin from remaining on duty for decades in police departments throughout the nation. And also how to keep them from getting jobs with new departments after being fired despite their records of abuse of power, excessive force, or other wrongdoing in their interactions with the people they are supposed to protect.

As Goff points out, we’re not going to fix the situation with just three DOJ investigations each year of the thousands of U.S. police departments. We desperately need that realignment toward more nurturing investments that he lays out as substitutes for yet more investment in punishment. Every political candidate—whether running for city council or the presidency—should not be allowed to evade answering the question that Wagner asked: Will policing in the 21st century look different than it did in the 20th and 19th centuries? There’s no excuse for continuing down the same path we’ve traveled for hundreds of years.

Whether it’s Minneapolis or Albuquerque or Pittsburgh or East Haven or Seattle or New Orleans or Meridian or Los Angeles County or Maricopa County, consent decrees may well be “better than nothing.” But another dash of weak sauce just isn’t enough.

•••••••••••

Related:

- You can view Goff’s 22-minute TED talk here.

- Calls for Systemic Transformation of US Policing Follow Damning DOJ Report on Minneapolis PD