Ukraine’s top military commander, Gen. Valery Zaluzhny, had a candid interview with The Economist, where he admits what so many want to pretend isn’t happening—that the war is at a stalemate. Then he offered solutions to that impasse.

Let’s take a close look at what Zaluzhny revealed.

There was so much hope and hopium ahead of the spring/summer offensive. We hoped that Russia’s defensive lines would be brittle, the conscripts manning them ready to flee or surrender upon first contact.

And yet, early on, there were signs of trouble—like a video I shared of a small tree line operation by the Azov Brigade, in which a Russian holed up in a trench fought to the death despite several offers of surrender.

Whether it was bravery or fear, the last thing anyone wanted to see was fanatical fights to the death. And it doesn’t surprise me that when I looked for that video, I found it in a story titled “Russia’s lines won’t be easy to breach,” published on May 31. Yet even that somewhat realistic story was peppered with unrealized hopium. “My hope is that once the first lines are breached, Russia’s obvious lack of a mobile reserve and an empty backfield allows Ukraine to romp behind enemy lines, cutting off supplies and isolating the defenders,” I wrote. In reality, it took months for Ukraine to finally breach the lines in the Robotyne area, and it never even reached those lines elsewhere on the front. And then not only did Russia prove to have sufficient reserves to plug the gap, but it also had several hundred additional vehicles and thousands of men to throw to slaughter around Avdiivka.

I wrote about an “obvious lack of a mobile reserve,” and I couldn’t have been more off—and I was one of the less optimistic war analysts. That’s why even now, so many Ukraine supporters cringe at those of us who say the war is at a stalemate. We don’t want it to be true. But Zaluzhny has conclusively put that debate to rest: “[W]e have reached the level of technology that puts us into a stalemate.”

What an excellent observation. Imagine if the U.S. lost 150,000 anywhere. The U.S. lost 2,354 servicemembers in Afghanistan and 4,431 in Iraq, and those losses—nearly 7,000 over 20 years—were unbearably high for our nation. Russia lost at least 150,000 in a little over a year and a half, and they don’t care, and it makes sense how you consider their fetishization of the millions they lost in WWII. Compared to that, 150,000 truly is small fries to someone like Vladimir Putin!

One other point: Note that Zaluzhny says “at least 150,000 dead.” This is what the Ukrainian ministry of defense claims:

People have long suspected that their “eliminated personnel” figure included wounded Russians, making the number far more plausible and believable. It’s amusing to see Ukraine’s top general inadvertently confirm the official claims are bullshit.

Back to the Economist:

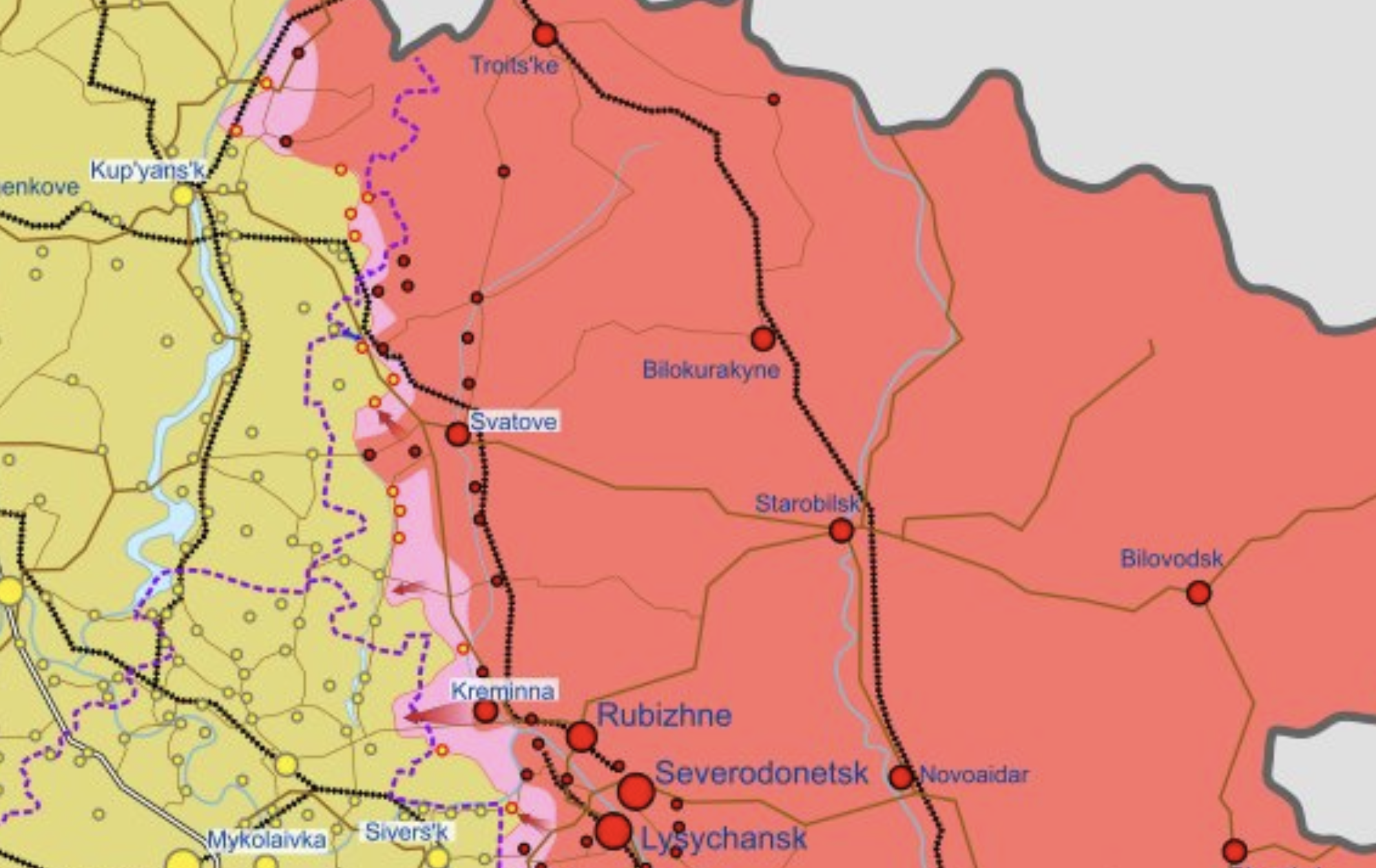

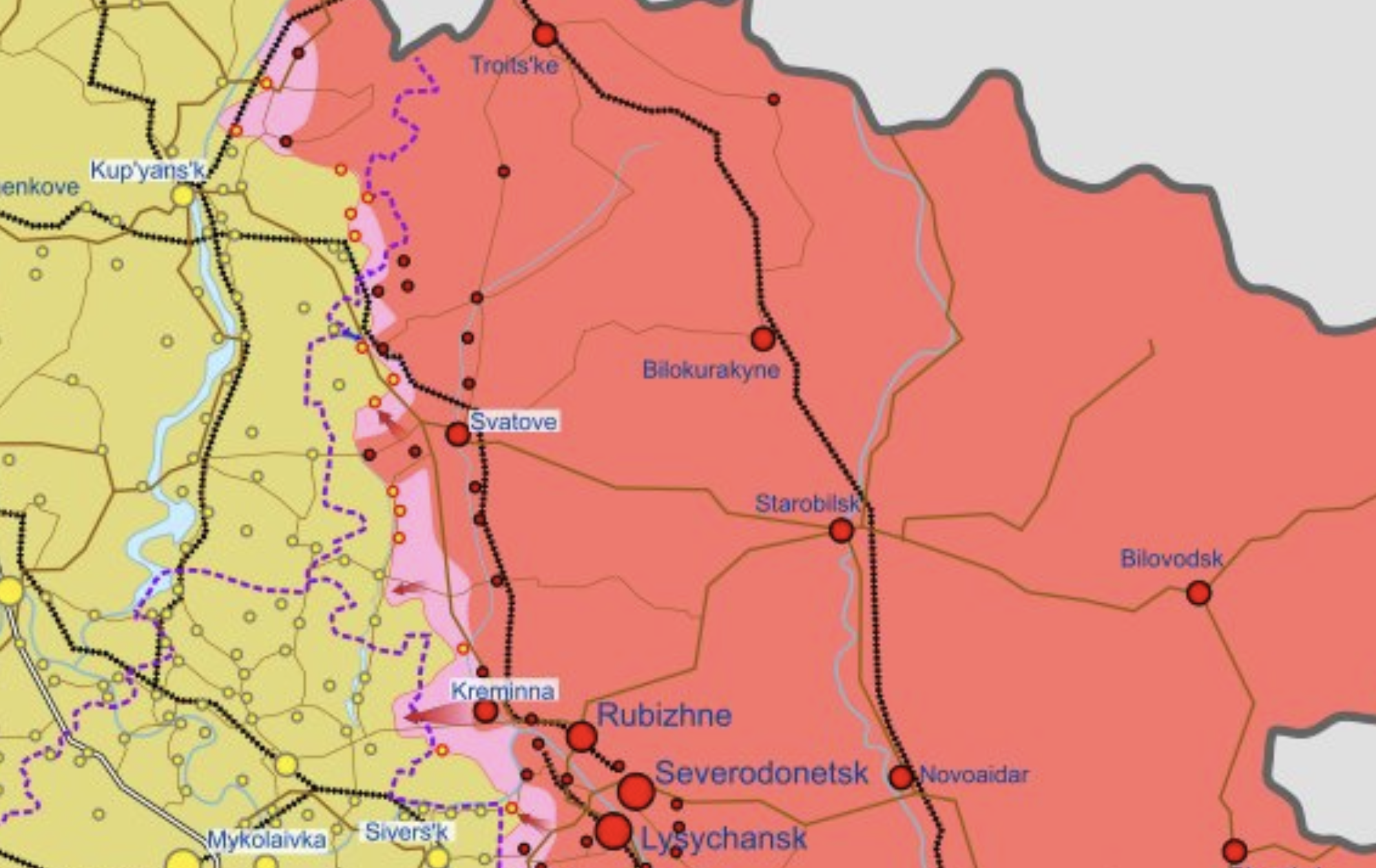

I don’t remember anyone thinking Ukraine would be able to romp to Crimea in four months. If that was really the thinking inside of Ukraine’s high command, no wonder they struck south at the heart of Russia’s strongest defenses, rather than make a line for Starobilsk in the north to cut off one of Russia’s two main supply routes to their invasion forces. I bet if they knew then what they know now, they would strike up north, in the face of much thinner Russian lines, liberating a ginormous block of land and giving Western donors an obvious return on their investments.

Retaking Starobilsk would liberate thousands of square miles of Russian-held territory, as every single supply line in the region intersects the city

Cutting the land bridge joining mainland Russia to Crimea offered a much higher reward than liberating Starobilsk, but it’s clear the land bridge isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

It was also clear (because I wrote about it incessantly before the offensive) that Ukraine would be hard-pressed to quickly train its forces properly in modern combined arms warfare. Too many people say trite things like “Ukrainians are smart and they learn fast.” And to a certain extent, their existential threat accelerates their progress. But there’s a difference between not taking weekends off, and learning the kinds of complex maneuvers—both at the command staff level, and at the ground levels—that would’ve increased Ukraine’s chances of success. That can take years to master.

This is why the “get F-16s to Ukraine ASAP” crowd is so misguided. F-16 fighter jets will arrive when their pilots are ready, and that’s definitely not something anyone wants to rush. The war will still be here in six to 12 months, so it’s best to ensure that the pilots are as well prepared for combat as possible. The last thing Ukraine needs is the unnecessary flaming wreckage of invaluable F-16s. Accidents happen in peacetime, in the best of circumstances. They are only accelerated in the stresses of combat. (That’s not to say that training shouldn’t have been approved earlier, but that’s a whole separate issue.)

Drones.

He’s talking about drones.

I don’t think people have fully internalized what a dramatic change that drones have wrought in modern warfare. Imagine, in World War II, if Germany had a fleet of drones watching the entire French coastline at all times. And in Afghanistan and Iraq, American losses would’ve been a lot higher if hostile militias could track the approach of American forces 24 hours a day.

Some of those changes are welcome—anything that deters a hostile force from war is likely a net positive. China has to know its Taiwan invasion contingency plans are all obsolete, given that any naval flotilla would be met by a swarm of anti-ship drones (from the air, the surface, and underwater). China could very well lay waste to Taiwan via aerial bombardment, but its chances of setting foot on the island under hostile conditions is fading by the day.

So while it’s all great for Taiwan, it’s less great for Ukraine, who has to deal with occupying Russians without a technological advantage to break through the stalemate.

In a separate piece, authored by Zaluzhny himself, he states what Ukraine needs to win:

I doubt that Ukraine will ever have full control over its skies, just like Russia will never have its own air superiority, afraid to venture beyond its front lines. But anything that pushes Russian warplanes even further back means whatever bombs they drop will be less accurate and impactful than is currently the place. Luckily, a few dozen F-16s armed with long-range air-to-air missiles will do that.

Many dream that F-16s can provide close air support to Ukrainian forces, but that’s just not going to happen. The F-16s will be too valuable to risk that close to Russian air defenses. But as a way to push Russia’s air force and navy further away? It should manage that nicely.

(Note: His number of destroyed air defense systems matches official claims.)

Yes, Ukraine desperately needs this. I’d go so far as to say everyone needs this. Ukraine is a perfect testing ground for Western experiments in how to best neutralize the drone threat. Because sooner or later, NATO nations will face the same threats. And we’re not even talking about an all-out war. What’s stopping a group of terrorists from launching a barrage of drones at a political rally? A soccer game in Munich, with 70,000 in the stands? A crowded shopping area? Tourists milling around the Eiffel Tower?

Pandora’s box has been opened, and it is in everyone’s interest to shut that thing down as quickly as possible. Ukraine is part of the solution.

By all indications (including assessments from both sides), Ukraine is doing an incredible job of eliminating Russian artillery. Zaluzhny’s concerns here go back to the drone one. If Russia needs drones to hit longer-range Western artillery, well, that’s not an artillery problem, it’s a drone problem. But yes, by all means, sending Ukraine all the counterbattery radars and munitions it needs to end the Russian artillery threat.

His fourth need is a tough one:

This is all new stuff. I don’t think it exists, but Ukraine is ready to innovate for solutions that, frankly, will benefit all of NATO. Please proceed.

His final need is more training capacity for Ukraine’s forces outside its territory. Thousands are being trained in the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, and other European countries. Seems like a no-brainer to expand that effort, not just for basic training, which needs to be extended. (My son trained for seven months to be an infantryman, and the training programs for Ukrainian soldiers last around four weeks). More experienced forces need to be rotated out and trained up on tactics and maneuvers. They’ve learned to hold their own under intense fire, conquering fear. Now give them the smarts they need to be even deadlier on the battlefield.

It is laudable that Zaluzhny was this open and candid about Ukraine’s challenges and needs. This war won’t end quickly; there is no quick-fix solution. But his requests here are reasonable and realistic, and will build the force—and technological edge—Ukraine needs to finally win this war.

Campaign Action

Let’s take a close look at what Zaluzhny revealed.

Sharing his first comprehensive assessment of the campaign with The Economist in an interview this week, Ukraine’s commander-in-chief, General Valery Zaluzhny, says the battlefield reminds him of the great conflict of a century ago. “Just like in the first world war we have reached the level of technology that puts us into a stalemate,” he says. The general concludes that it would take a massive technological leap to break the deadlock. “There will most likely be no deep and beautiful breakthrough.”

There was so much hope and hopium ahead of the spring/summer offensive. We hoped that Russia’s defensive lines would be brittle, the conscripts manning them ready to flee or surrender upon first contact.

And yet, early on, there were signs of trouble—like a video I shared of a small tree line operation by the Azov Brigade, in which a Russian holed up in a trench fought to the death despite several offers of surrender.

Whether it was bravery or fear, the last thing anyone wanted to see was fanatical fights to the death. And it doesn’t surprise me that when I looked for that video, I found it in a story titled “Russia’s lines won’t be easy to breach,” published on May 31. Yet even that somewhat realistic story was peppered with unrealized hopium. “My hope is that once the first lines are breached, Russia’s obvious lack of a mobile reserve and an empty backfield allows Ukraine to romp behind enemy lines, cutting off supplies and isolating the defenders,” I wrote. In reality, it took months for Ukraine to finally breach the lines in the Robotyne area, and it never even reached those lines elsewhere on the front. And then not only did Russia prove to have sufficient reserves to plug the gap, but it also had several hundred additional vehicles and thousands of men to throw to slaughter around Avdiivka.

I wrote about an “obvious lack of a mobile reserve,” and I couldn’t have been more off—and I was one of the less optimistic war analysts. That’s why even now, so many Ukraine supporters cringe at those of us who say the war is at a stalemate. We don’t want it to be true. But Zaluzhny has conclusively put that debate to rest: “[W]e have reached the level of technology that puts us into a stalemate.”

The course of the counter-offensive has undermined Western hopes that Ukraine could use it to demonstrate that the war is unwinnable, forcing Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, to negotiate. It has also undercut General Zaluzhny’s assumption that he could stop Russia by bleeding its troops. “That was my mistake. Russia has lost at least 150,000 dead. In any other country such casualties would have stopped the war.” But not in Russia, where life is cheap and where Mr Putin’s reference points are the first and second world wars, in which Russia lost tens of millions.

What an excellent observation. Imagine if the U.S. lost 150,000 anywhere. The U.S. lost 2,354 servicemembers in Afghanistan and 4,431 in Iraq, and those losses—nearly 7,000 over 20 years—were unbearably high for our nation. Russia lost at least 150,000 in a little over a year and a half, and they don’t care, and it makes sense how you consider their fetishization of the millions they lost in WWII. Compared to that, 150,000 truly is small fries to someone like Vladimir Putin!

One other point: Note that Zaluzhny says “at least 150,000 dead.” This is what the Ukrainian ministry of defense claims:

"Out of all this struggle a good thing is going to grow. That makes it worthwhile." John Steinbeck The combat losses of the enemy from February 24, 2022 to November 3, 2023. pic.twitter.com/NDAHhfraBk

— Defense of Ukraine (@DefenceU) November 3, 2023

People have long suspected that their “eliminated personnel” figure included wounded Russians, making the number far more plausible and believable. It’s amusing to see Ukraine’s top general inadvertently confirm the official claims are bullshit.

Back to the Economist:

An army of Ukraine’s standard ought to have been able to move at a speed of 30km a day as it breached Russian lines. “If you look at nato’s text books and at the maths which we did, four months should have been enough time for us to have reached Crimea, to have fought in Crimea, to return from Crimea and to have gone back in and out again,” General Zaluzhny says sardonically. Instead he watched his troops get stuck in minefields on the approaches to Bakhmut in the east, his Western-supplied equipment getting pummelled by Russian artillery and drones. The same story unfolded on the offensive’s main thrust in the south, where inexperienced brigades immediately ran into trouble.

I don’t remember anyone thinking Ukraine would be able to romp to Crimea in four months. If that was really the thinking inside of Ukraine’s high command, no wonder they struck south at the heart of Russia’s strongest defenses, rather than make a line for Starobilsk in the north to cut off one of Russia’s two main supply routes to their invasion forces. I bet if they knew then what they know now, they would strike up north, in the face of much thinner Russian lines, liberating a ginormous block of land and giving Western donors an obvious return on their investments.

Retaking Starobilsk would liberate thousands of square miles of Russian-held territory, as every single supply line in the region intersects the city

Cutting the land bridge joining mainland Russia to Crimea offered a much higher reward than liberating Starobilsk, but it’s clear the land bridge isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

It was also clear (because I wrote about it incessantly before the offensive) that Ukraine would be hard-pressed to quickly train its forces properly in modern combined arms warfare. Too many people say trite things like “Ukrainians are smart and they learn fast.” And to a certain extent, their existential threat accelerates their progress. But there’s a difference between not taking weekends off, and learning the kinds of complex maneuvers—both at the command staff level, and at the ground levels—that would’ve increased Ukraine’s chances of success. That can take years to master.

This is why the “get F-16s to Ukraine ASAP” crowd is so misguided. F-16 fighter jets will arrive when their pilots are ready, and that’s definitely not something anyone wants to rush. The war will still be here in six to 12 months, so it’s best to ensure that the pilots are as well prepared for combat as possible. The last thing Ukraine needs is the unnecessary flaming wreckage of invaluable F-16s. Accidents happen in peacetime, in the best of circumstances. They are only accelerated in the stresses of combat. (That’s not to say that training shouldn’t have been approved earlier, but that’s a whole separate issue.)

“First I thought there was something wrong with our commanders, so I changed some of them. Then I thought maybe our soldiers are not fit for purpose, so I moved soldiers in some brigades,” says General Zaluzhny. When those changes failed to make a difference, the general told his staff to dig out a book he once saw as a student. Its title was “Breaching Fortified Defence Lines”. It was published in 1941 by a Soviet major-general, P.S. Smirnov, who analysed the battles of the first world war. “And before I got even halfway through it, I realised that is exactly where we are because just like then, the level of our technological development today has put both us and our enemies in a stupor.”

Drones.

He’s talking about drones.

That thesis, he says, was borne out as he went to the front line in Avdiivka, also in the east, where Russia has recently advanced by a few hundred metres over several weeks by throwing in two of its armies. “On our monitor screens the day I was there we saw 140 Russian machines ablaze—destroyed within four hours of coming within firing range of our artillery.” Those fleeing were chased by “first-person-view” drones, remote-controlled and carrying explosive charges that their operators simply crash into the enemy. The same picture unfolds when Ukrainian troops try to advance.

I don’t think people have fully internalized what a dramatic change that drones have wrought in modern warfare. Imagine, in World War II, if Germany had a fleet of drones watching the entire French coastline at all times. And in Afghanistan and Iraq, American losses would’ve been a lot higher if hostile militias could track the approach of American forces 24 hours a day.

Some of those changes are welcome—anything that deters a hostile force from war is likely a net positive. China has to know its Taiwan invasion contingency plans are all obsolete, given that any naval flotilla would be met by a swarm of anti-ship drones (from the air, the surface, and underwater). China could very well lay waste to Taiwan via aerial bombardment, but its chances of setting foot on the island under hostile conditions is fading by the day.

So while it’s all great for Taiwan, it’s less great for Ukraine, who has to deal with occupying Russians without a technological advantage to break through the stalemate.

In a separate piece, authored by Zaluzhny himself, he states what Ukraine needs to win:

Ukrainians have shown their willingness to lay down soul and body for their freedom. Ukraine not only halted an invasion by a far stronger enemy but liberated much of its territory. However, the war is now moving to a new stage: what we in the military call “positional” warfare of static and attritional fighting, as in the first world war, in contrast to the “manoeuvre” warfare of movement and speed. This will benefit Russia, allowing it to rebuild its military power, eventually threatening Ukraine’s armed forces and the state itself. What is the way out?

Basic weapons, such as missiles and shells, remain essential. But Ukraine’s armed forces need key military capabilities and technologies to break out of this kind of war. The most important one is air power. Control of the skies is essential to large-scale ground operations. At the start of the war we had 120 warplanes. Of these, only one-third were usable.

Russia’s air force has taken huge losses and we have destroyed over 550 of its air-defence systems, but it maintains a significant advantage over us and continues to build new attack squadrons. That advantage has made it harder for us to advance. Russia’s air-defence systems increasingly prevent our planes from flying. Our defences do the same to Russia. So Russian drones have taken over a large part of the role of manned aviation in terms of reconnaissance and air strikes.

I doubt that Ukraine will ever have full control over its skies, just like Russia will never have its own air superiority, afraid to venture beyond its front lines. But anything that pushes Russian warplanes even further back means whatever bombs they drop will be less accurate and impactful than is currently the place. Luckily, a few dozen F-16s armed with long-range air-to-air missiles will do that.

Many dream that F-16s can provide close air support to Ukrainian forces, but that’s just not going to happen. The F-16s will be too valuable to risk that close to Russian air defenses. But as a way to push Russia’s air force and navy further away? It should manage that nicely.

(Note: His number of destroyed air defense systems matches official claims.)

Drones must be part of our answer, too. Ukraine needs to conduct massive strikes using decoy and attack drones to overload Russia’s air-defence systems. We need to hunt down Russian drones using our own hunter drones equipped with nets. We must use signal-emitting decoys to attract Russian glide bombs. And we need to blind Russian drones’ thermal cameras at night using stroboscopes.

This points to our second priority: electronic warfare (ew), such as jamming communication and navigation signals. EW is the key to victory in the drone war. Russia modernised its EW forces over the past decade, creating a new branch of its army and building 60 new types of equipment. It outdoes us in this area: 65% of our jamming platforms at the start of the war were produced in Soviet times.

We have already built many of our own electronic protection systems, which can prevent jamming. But we also need more access to electronic intelligence from our allies, including data from assets that collect signals intelligence, and expanded production lines for our anti-drone EW systems within Ukraine and abroad. We need to get better at conducting electronic warfare from our drones, across a wider range of the radio spectrum, while avoiding accidental suppression of our own drones.

Yes, Ukraine desperately needs this. I’d go so far as to say everyone needs this. Ukraine is a perfect testing ground for Western experiments in how to best neutralize the drone threat. Because sooner or later, NATO nations will face the same threats. And we’re not even talking about an all-out war. What’s stopping a group of terrorists from launching a barrage of drones at a political rally? A soccer game in Munich, with 70,000 in the stands? A crowded shopping area? Tourists milling around the Eiffel Tower?

Pandora’s box has been opened, and it is in everyone’s interest to shut that thing down as quickly as possible. Ukraine is part of the solution.

Meanwhile, Russia’s own counter-battery fire has improved. This is largely thanks to its use of Lancet loitering munitions, which work alongside reconnaissance drones, and its increasing production of precision-guided shells that can be aimed by ground spotters. Despite the dismissive view of some military analysts, we cannot belittle the effectiveness of Russian weapons and intelligence in this regard.

For now, we have managed to achieve parity with Russia through a smaller quantity of more accurate firepower. But this may not last. We need to build up our local GPS fields—using ground-based antennas rather than just satellites—to make our precision-guided shells more accurate in the face of Russian jamming. We need to make greater use of kamikaze drones to strike Russian artillery. And we need our partners to send us better artillery-reconnaissance equipment that can locate Russian guns.

By all indications (including assessments from both sides), Ukraine is doing an incredible job of eliminating Russian artillery. Zaluzhny’s concerns here go back to the drone one. If Russia needs drones to hit longer-range Western artillery, well, that’s not an artillery problem, it’s a drone problem. But yes, by all means, sending Ukraine all the counterbattery radars and munitions it needs to end the Russian artillery threat.

His fourth need is a tough one:

The fourth task is mine-breaching technology. We had limited and outdated equipment for this at the start of the war. But even Western supplies, such as Norwegian mine-clearing tanks and rocket-powered mine-clearing devices, have proved insufficient given the scale of Russian minefields, which stretch back 20km in places. When we do breach minefields, Russia quickly replenishes them by firing new mines from a distance.

Technology is the answer. We need radar-like sensors that use invisible pulses of light to detect mines in the ground and smoke-projection systems to conceal the activities of our de-mining units. We can use jet engines from decommissioned aircraft, water cannons or cluster munitions to breach mine barriers without digging into the ground. New types of tunnel excavators, such as a robot which uses plasma torches to bore tunnels, can also help.

This is all new stuff. I don’t think it exists, but Ukraine is ready to innovate for solutions that, frankly, will benefit all of NATO. Please proceed.

His final need is more training capacity for Ukraine’s forces outside its territory. Thousands are being trained in the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, and other European countries. Seems like a no-brainer to expand that effort, not just for basic training, which needs to be extended. (My son trained for seven months to be an infantryman, and the training programs for Ukrainian soldiers last around four weeks). More experienced forces need to be rotated out and trained up on tactics and maneuvers. They’ve learned to hold their own under intense fire, conquering fear. Now give them the smarts they need to be even deadlier on the battlefield.

It is laudable that Zaluzhny was this open and candid about Ukraine’s challenges and needs. This war won’t end quickly; there is no quick-fix solution. But his requests here are reasonable and realistic, and will build the force—and technological edge—Ukraine needs to finally win this war.

Campaign Action